Loving Like Christ in Conflict

As a counselor, I am often asked what constitutes a healthy relationship. The reality is that every relationship is different. What works in one relationship may not work in another. What is working now in a relationship may not work later. This makes healthiness in the context of relationships difficult to define, but after years of working with couples, I have identified some relationship trends that I can generally say are unhealthy.

CODEPENDENCE: An Unhealthy Way to Love Others

One term that is often thrown around relating to unhealthy relationships is the word “codependence.” Many people use the term without any understanding of what it means. In some ways, it has become such a nebulous concept that it means almost nothing. Originally, the term was used to describe unhealthy relationships with addicts where the non-addicted partner would enable their addicted partner. Today, codependence can be identified in almost every relationship between intimate partners, friends, or even organizations. I think it is easiest to understand in intimate relationships, but organizational codependence is also an important consideration for us as Salvationists.

Codependence is most simply defined as any unhealthy dependence. As you can tell, this definition is very loose and requires further definition of both “unhealthy” and “dependence.”

Dependence is when we require someone or something else to meet our needs. There are healthy dependencies. For example, all working adults are dependent upon their employer to pay their paycheck, and the employer is dependent upon the employee to do their job. This can be unbalanced into a codependent relationship if the employer or the employee fails to follow through on their obligations. If you are working for your employer without getting paid, the relationship is now unhealthy for you. Similarly, if you are not doing your job and are still being paid, the relationship is now unhealthy for the employer.

One complicated factor is that some relationships are naturally unbalanced. For example, if a spouse experiences severe medical issues, they may become more dependent upon their partner in an unbalanced way. They will be taking more from the healthy partner. It could be argued that this relationship is codependent because it would be more beneficial for the healthy partner to leave. While I think this relationship is codependence-prone, it is not naturally codependent. In this example, one spouse cannot meet their own needs, and they must be met by another person, making them naturally dependent. Being dependent upon someone else to meet your needs when you cannot fulfill the need yourself is not codependent. The relationship becomes codependent when one person can meet their own needs but chooses not to. This is an unhealthy taking rather than a healthy taking from the relationship.

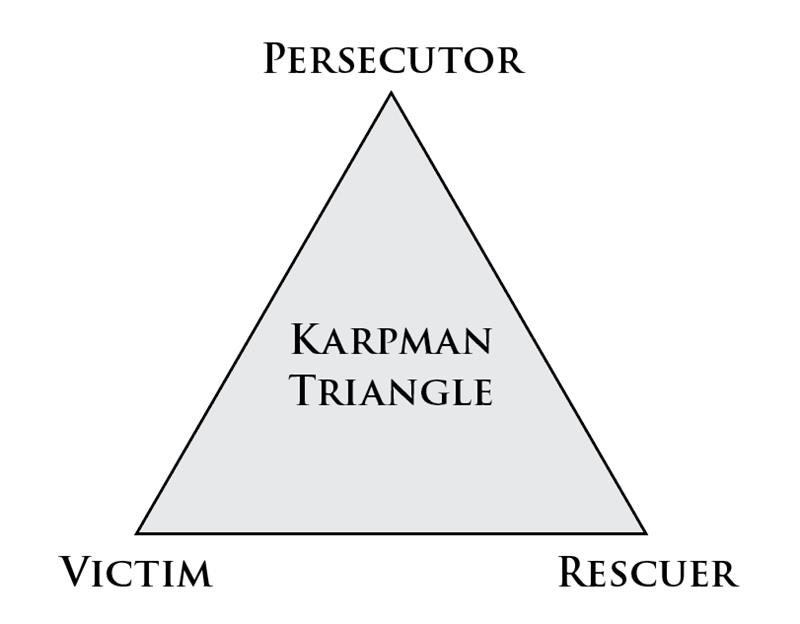

As you can see, distinguishing a healthy dependence from an unhealthy dependence is a complicated task. A healthy dependence can quickly become an unhealthy dependence, unbalancing a relationship. One way to identify codependent relationships is by using the Karpman Triangle.

THE KARPMAN TRIANGLE: Unhealthy Dynamics

The triangle consists of three unhealthy roles that people play when they experience conflict in a relationship: persecutor, victim, and rescuer. When there is conflict, people slide around in these roles until the other person concedes and agrees to meet their need, whatever that need might be. Once you learn this concept, you will see it everywhere in just about every conflict.

The Persecutor

The persecutor role is that of the hypercritical parent. They are on the attack. They are going to act in their own best interest and use the tools of shame, rejection, and condemnation to get their way. When they are playing this role, they lack empathy, discount other people’s pain, and attack the “self” of the other person. They believe that they are in the right and the other person is totally wrong, therefore they need to punish or shame the other person until they comply. The persecutor’s dominant emotion is anger. They are angry at others for not meeting their needs, and they are afraid of not being valued or heard.

The Victim

The victim takes on the role of the helpless child. They are usually suffering, but most importantly, they discount their own ability to fix their problems or meet their needs. They act as if they could never solve their own problem and are completely powerless. Very often they play the victim role to seek attention or to get out of taking responsibility for their own situation. They believe that things will never be okay unless you fix it for them. The dominant emotions they feel are fear, helplessness, and hopelessness. However, under the surface they often feel anger at being treated like a child and resentment toward those trying to help them. They are afraid that they are unable to deal with life on life’s terms and will never be happy.

The Rescuer

The rescuer adopts the position of the overly nurturing parent. They take over all problem solving and go above and beyond to fix someone else’s problem. They often do things for others that they could easily do for themselves, discounting other people’s ability to function and solve their own problems. Their dominant belief is that things will not be okay unless they step in to fix things. Their dominant emotion is anxiety, but under the surface they are angry that they always have to be the fixer. They have a fear that others will be angry at them if they say no or set boundaries. They are afraid that everything will fall apart if they don’t play their role.

As you were reading those last three paragraphs, I am sure the descriptions brought to mind people that you know. You may have even recognized times that you played these roles in a conflict. When I observe conflicts, I often see people oscillating between the victim and persecutor roles to get the other person to be the rescuer. I know people who constantly play the persecutor role to get their way. People around them often step into the rescuer role just to avoid conflict. “If I don’t do this, they will be mad at me, so I have to fix things.” Others prefer playing the victim role knowing that someone will step in and fix their problems if they just complain enough. Skilled manipulators will slide through all these roles until they win the conflict. Here is one example: “You are just like your father (Persecutor)! You don’t know all the ways he hurt me (Victim). But it’s okay, I’ll make sure you don’t turn out like him (Rescuer).”

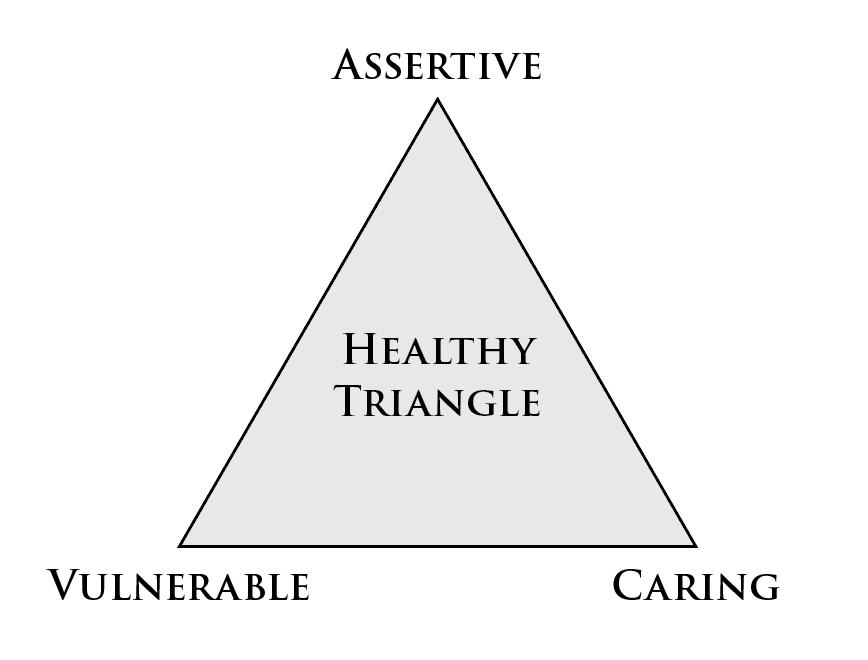

HEALTHY CONFLICT ROLES

While these roles are unhealthy, there are ways to approach conflict in a healthy way. The healthy version of the Karpman Triangle has similar roles, but with a healthy twist. They are: assertive, vulnerable, and caring.

Assertive

An assertive person knows their own wants and needs and expresses them calmly. They are comfortable saying no and are also willing to compromise. Importantly, rather than being self-centered, they take the needs of others into account. They believe that their thoughts and feelings are important, and they are willing to listen to the thoughts and feelings of others. The dominant emotions they feel are relaxed, centered, and confident. To adopt the assertive role, one needs to be skilled in communication and setting boundaries.

Vulnerable

A vulnerable person is like the victim in that they are suffering or potentially suffering. They know their own limits and are willing to ask for help when needed. They care for themselves as needed, communicate their needs, and accept support. Their dominant feeling is hope. They have a fundamental belief that they can improve their own situation but are still okay if they feel down during the process. The vulnerable person needs to be skilled in boundary setting and problem solving while having an internal locus of control and self-efficacy.

Caring

A caring person has legitimate concern for the vulnerable but encourages independent thinking. They separate their own responsibility from the responsibility of others. They offer help but do no more than their share. They respect the wishes of the vulnerable person if they do not want help. They accept that they are often powerless to fix other people’s problems but will help in any healthy ways they can. Their dominant emotion is empathy, and they must be skilled in listening and boundaries.

You can see that the key difference between the healthy triangle and the unhealthy triangle comes down to boundaries and self-responsibility. A healthy person takes responsibility for their own problems, acknowledges their limitations, and asks for help when needed. An unhealthy person will not take responsibility, tries to get other people to fix their problems, and takes on way too much responsibility when they help others.

CODEPENDENCE IN MINISTRY

In my work with people from The Salvation Army, I find that we attract people who like to be in the rescuer role. I have seen many officers and soldiers who overcommit and try to fix other people’s problems. This leads to the natural result of burnout. As members of The Salvation Army, we need to be caring leaders in our communities. We need to know our own limitations and ask for help when we need it. At the same time, we need to avoid overcommitment and taking on too much responsibility for meeting the needs of others. The problem is that we like the feeling of power that comes with being in the rescuer role.

When I worked in the Adult Rehabilitation Center (ARC), I saw the Karpman Triangle playing out every day. We had beneficiaries who were experts at playing the different roles to avoid responsibility for their actions and getting their way. The single most dangerous thing to do is to take on the rescuer role with an addict. They learn very quickly that if they want you to do something, all they have to do is play the victim and you will give them whatever they want. The beneficiaries in the ARC are legitimately suffering, but the key to fixing their situation is them taking responsibility for their own actions and making the needed changes in their life. In this situation, the rescuer protecting the addict from the consequences of their actions actually makes things worse, taking on the responsibility for meeting the addict’s needs so they do not have to change their ways and get sober.

When you enter the rescuer role in the attempt to help someone, you make the situation worse. You teach them that they do not have to take responsibility as long as they take on the victim or the persecutor roles. So, whenever they are faced with a challenge, they know that they don’t have to overcome it if you are there. They never learn how to help themselves. They never learn how to fix their own problems. What they learn is to give up whenever life gets hard and wait for someone else to fix their problems. This behavior is not healthy for everyone.

AN ARMY OF LOVE

We need to be an Army of caring people. We need to empower others to fix their own situations and problems. We need to generate lasting change in our communities through the power of Jesus Christ. We need to acknowledge our own limitations. We cannot take responsibility for other people’s problems. We can point them in the right direction. We can meet their immediate needs. But if that is not followed by them taking responsibility for their own problems, we are making our communities worse, not better.

The problem is that we like it when people are dependent upon us. We think that when they are dependent on us, they are less likely to abandon us. What leads us into unhealthy relationships is our fear of rejection. We think that if we just keep playing our rescuer role, they won’t leave us. To operate on the healthy triangle, we need to overcome our abandonment issues and fear of rejection.

Here are some questions to consider:

- What are some codependent relationships in my life? Are any of my relationships unbalanced?

- When do I enter the Karpman Triangle? What role do I usually play when I am in the triangle?

- What boundaries do I need to set to free myself from the Karpman Triangle? Who do I need to set those boundaries with?